Understanding Film Cameras: A Guide to SLRs, Rangefinders, Point-and-Shoots, and TLRs

Understanding Film Cameras: A Complete Guide to SLRs, Rangefinders, Point-and-Shoots, and TLRs

Quick Summary

If you’re exploring film photography or expanding your collection, understanding the various types of film cameras is essential. From versatile SLRs to unique TLRs, each type offers distinct benefits, challenges, and creative opportunities. Whether you’re looking for full manual control, portability, or a unique shooting experience, this guide should help you navigate the options.

Key Takeaways:

- SLRs (Single-Lens Reflex): Great for beginners, offering full manual control, interchangeable lenses, and a true-to-life view through the lens.

- Rangefinders: Quiet, lightweight, and ideal for street or travel photography, though they require practice to master focusing.

- Point-and-Shoot Cameras: Compact and fully automatic, perfect for casual use and quick snaps.

- TLRs (Twin-Lens Reflex): Vintage charm, excellent for medium-format photography and portrait work, but require more time and precision to use.

Camera Type 1: SLR (Single-Lens Reflex)

Introduction

SLRs are arguably the most accessible type of film camera for beginners and experienced photographers alike. They use a mirror and prism system to reflect the image seen through the lens into the viewfinder, providing a direct preview of your shot.

How SLRs Work

The defining feature of an SLR is its mirror mechanism. Here’s how it functions:

- Viewing: When you look through the viewfinder, light enters through the lens and hits a mirror positioned at a 45-degree angle inside the camera. This light is then reflected upwards to a pentaprism (or pentamirror), which flips the image and displays it correctly in the viewfinder.

- Focusing and Composition: Because you’re seeing exactly what the lens sees, you can accurately compose and focus your shot.

- Taking the Shot: When you press the shutter button, the mirror flips up, and the light hits the film directly. At the same time, the shutter opens for the set duration, allowing light to expose the film.

- Reset: After the exposure, the mirror returns to its original position, and the camera is ready for the next shot.

This mirror mechanism is what distinguishes SLRs from other types of cameras, as it provides a true-to-life preview of the scene you’re capturing.

Key Points

Pros:

- Interchangeable Lenses: SLRs offer a wide range of lenses, allowing you to experiment with different focal lengths and effects.

- Manual Control: Perfect for learning photography fundamentals (like the Sunny 16 Rule)

- Durability: Many classic SLRs are built to last decades.

Cons:

- Size and Weight: Bulkier compared to other camera types.

- Noise: The mirror mechanism can be loud.

Best For:

SLRs are ideal for beginners, general-purpose photography, and anyone looking to have creative control. Much of my photography portfolio is taken with SLRs.

Examples: Canon AE-1, Nikon FM2, Pentax K1000.

Camera Type 2: Rangefinders

Introduction

Rangefinders offer a unique shooting experience, relying on a separate viewfinder for composition and focusing. This makes them lighter and quieter than SLRs, but they require a bit more skill to master.

How Rangefinders Work

The key difference in rangefinders is their separate focusing mechanism:

- Viewfinder System: The viewfinder is offset from the lens, meaning you’re not looking through the lens itself. Instead, you see a slightly different perspective of the scene.

- Focusing: Rangefinders use a split-image focusing system. Inside the viewfinder, you’ll see two overlapping images of your subject. As you adjust the focus, these images align, indicating that your subject is in focus.

- Parallax Effect: Because the viewfinder is separate from the lens, the framing may not perfectly match what the lens captures, especially at close distances. This is known as parallax error and is most noticeable in macro or close-up photography.

Rangefinders are favoured for their compact size and quiet operation, making them perfect for street photography.

Key Points

Pros:

- Quiet Operation: Ideal for discreet shooting.

- Compact and Lightweight: Great for travel or street photography.

- Sharp Lenses: Rangefinders often come with high-quality, fast lenses.

Cons:

- Focusing Learning Curve: The split-image system requires practice.

- Framing Limitations: Parallax error can affect composition.

Best For:

Rangefinders excel in street and travel photography and are perfect for photographers who value portability.

Examples: Leica M6, Canonet QL17, Yashica Electro 35, Canon P

Camera Type 3: Point-and-Shoot Cameras

Introduction

Point-and-shoot cameras are compact, fully automatic cameras designed for ease of use. They’re a fantastic option for casual photographers or those who want a simple, no-fuss shooting experience.

How Point-and-Shoot Cameras Work

Point-and-shoot cameras automate nearly every aspect of photography:

- Lens: Most have a fixed lens with a general-purpose focal length, such as 35mm or 50mm.

- Focusing: Autofocus systems handle focusing for you, ensuring sharp images without manual input.

- Exposure: The camera automatically adjusts shutter speed and aperture based on the light conditions, so you don’t need to worry about settings.

- Shooting: Simply aim, compose your shot in the viewfinder or LCD screen, and press the shutter button.

The simplicity of point-and-shoot cameras makes them ideal for quick, spontaneous photography.

Key Points

Pros:

- Simplicity: Perfect for beginners or casual use.

- Compact and Lightweight: Easy to carry anywhere.

- Affordable Options: Many models are inexpensive.

Cons:

- Limited Control: You can’t manually adjust settings.

- Quality Variability: Image quality depends heavily on the model.

Best For:

Point-and-shoot cameras are great for beginners, casual photographers, or anyone wanting a no-fuss way to capture memories.

Examples: Olympus XA2, Konica Big Mini, Canon SureShot.

Camera Type 4: TLR (Twin-Lens Reflex)

Introduction

TLRs are vintage-style film cameras with two lenses: one for viewing and one for taking the photograph. Popular for medium-format photography, they are known for their unique shooting experience and incredible image quality.

How TLRs Work

The defining feature of a TLR is its twin-lens system:

- Viewing Lens: The upper lens projects the scene onto a ground-glass screen, viewed through a waist-level viewfinder. This gives you a clear preview of your shot, but the image is flipped horizontally, which can take some getting used to.

- Taking Lens: The lower lens captures the image onto the film. Because the two lenses are mechanically linked, adjustments to the viewing lens automatically apply to the taking lens.

- Manual Operation: Most TLRs are fully manual, requiring you to set focus, aperture, and shutter speed yourself.

- Film Format: TLRs typically use medium-format film (120) for larger negatives and incredible detail.

Key Points

Pros:

- Stunning Image Quality: Larger negatives provide exceptional detail.

- Vintage Charm: The waist-level viewfinder and tactile controls make shooting an experience in itself.

- Durability: Built to last and often fully mechanical.

Cons:

- Bulky: TLRs are heavier and less portable.

- Slower Operation: Requires time and patience to set up each shot.

- Learning Curve: The flipped viewfinder image can be disorienting at first.

Best For:

TLRs are ideal for portrait photographers, enthusiasts of medium-format film, or anyone seeking a unique shooting experience.

Examples: Rolleiflex 2.8, Yashica Mat-124G, Mamiya C330.

Conclusion

Choosing the right film camera depends on your experience level, creative goals, and personal preferences.

- SLRs are versatile and beginner-friendly, offering excellent control.

- Rangefinders excel in street and travel photography with their compact size and quiet operation.

- Point-and-shoot cameras are simple and perfect for casual or spontaneous photography.

- TLRs provide stunning image quality and a vintage charm, ideal for thoughtful, artistic photography, but are a step up in complexity.

Explore these options, and you’re sure to find a camera that suits your style. If you’re new to film photography in general, I would definitely recommend starting out with an affordable SLR.

Take a look at my beginner’s guide to film photography, too!

Fred Ostrovskis-Wilkes

I am a photographer, writer and design agency founder based in Sheffield, UK.

A Guide to the Different Types of Film Used in Film Photography

The Different Types of Film Used in Film Photography

Quick Summary

Film photography is an art form built on variety and creative expression, and one of the most exciting elements is the vast selection of film types available to photographers.

It can also be, to the beginner film photographer, the most intimidating!

Each type of film offers unique characteristics, from colour rendering to grain structure, meaning that the type of film you choose can significantly impact your final image (as well as your bank account…)

So, this is a blog for beginners all about film types and will hopefully give you an understanding of the differences between film types and the ability to make informed decisions when selecting film stocks for your projects.

Key Takeaways:

- Film comes in 35mm, medium, and large format

- 35mm film is the most common format for beginners, offering affordability, availability, and ease of use with 24-36 exposures per roll.

- 120 (medium format) film captures higher resolution images and greater detail but comes with fewer exposures and a steeper learning curve, as well as higher costs.

- Large format film delivers the highest image quality and resolution but is expensive, complex, and not suitable for beginners.

- Colour negative film is versatile, forgiving, and widely available, making it ideal for general photography and beginners.

- Black and white film offers a classic look and is easier to develop at home, making it a great choice for creative experimentation.

Film Formats Explained

A good place to start is by understanding the different formats available. Film format refers to the size of the film used, and different cameras are built for different formats.

Here are the three most common film formats in photography:

1. 35mm Film

- This is the most widely used film format, ideal for beginners due to its availability, affordability, and wide selection. It’s used in 35mm cameras, which are compact, easy to carry, and more affordable than larger format cameras.

- 35mm film produces a standard rectangular image with a typical frame size of 24mm x 36mm.

- Best For: General photography, street photography, and everyday shooting. It’s definitely my recommendation for those just starting out due to its simplicity and ease of use.

2. 120 Film (Medium Format)

- 120 film is larger than 35mm and used in medium format cameras. It captures more detail due to its larger negative size, which results in higher resolution images.

- The frame size varies depending on the camera (6×4.5, 6×6, 6×7, or even 6×9), producing rich detail and sharpness.

- Best For: Portraits, landscapes, or any scenario where image quality is a priority. However, it’s less forgiving for beginners due to higher cost and a more limited number of shots per roll (not to mention medium format cameras themselves!)

3. Large Format Film

- Large format film is typically sheet film rather than roll film, with sizes like 4×5 inches or 8×10 inches. It’s used in large format cameras, often by professional photographers or those seeking extremely high resolution.

- Large negatives offer unmatched detail, tonal range, and resolution, but large format cameras are bulky and more challenging to use.

- Best For: Fine art photography, architectural photography, and large-scale prints where image detail is critical.

Which Format is Best for Beginners?

For most beginners, 35mm film is the best choice. It’s cost-effective, easy to find online and in your local camera shop, and comes in a wide variety of film stocks.

The smaller size of 35mm film also means you get more exposures per roll (typically 24 or 36), making it great for practicing without breaking the bank.

If you’re looking for a challenge and want to explore more detailed images, 120 film (medium format) can be a fun step up once you’re more comfortable with the basics. However, large format film is generally not recommended for beginners due to its complexity and cost.

6 common Film types Used in Film Photography

1. Color Negative Film (C-41)

Colour negative film is the most common type of film used today.

This type of film is known for its versatility and ease of use. When you take a picture with this type of film, it produces a negative image (hence the name) which is then inverted during the printing or scanning process to create a positive, true-to-life colour photograph.

Characteristics:

- Dynamic Range: One of the key strengths of colour negative film is its wide dynamic range, meaning it can capture details in both shadows and highlights.

- Exposure Latitude: Colour negative film is very forgiving with exposure, meaning if you over- or under-expose a shot slightly, you’ll still end up with a usable image (one of the reasons it’s great for beginners!)

- Popular Film Stocks: Kodak Gold 200, Kodak Portra, Kodak Ektar, and Fuji Pro 400H.

Best For:

- Portraits, landscapes, and everyday photography.

- Great for beginners due to its exposure flexibility, availability and cheaper initial cost and processing fees.

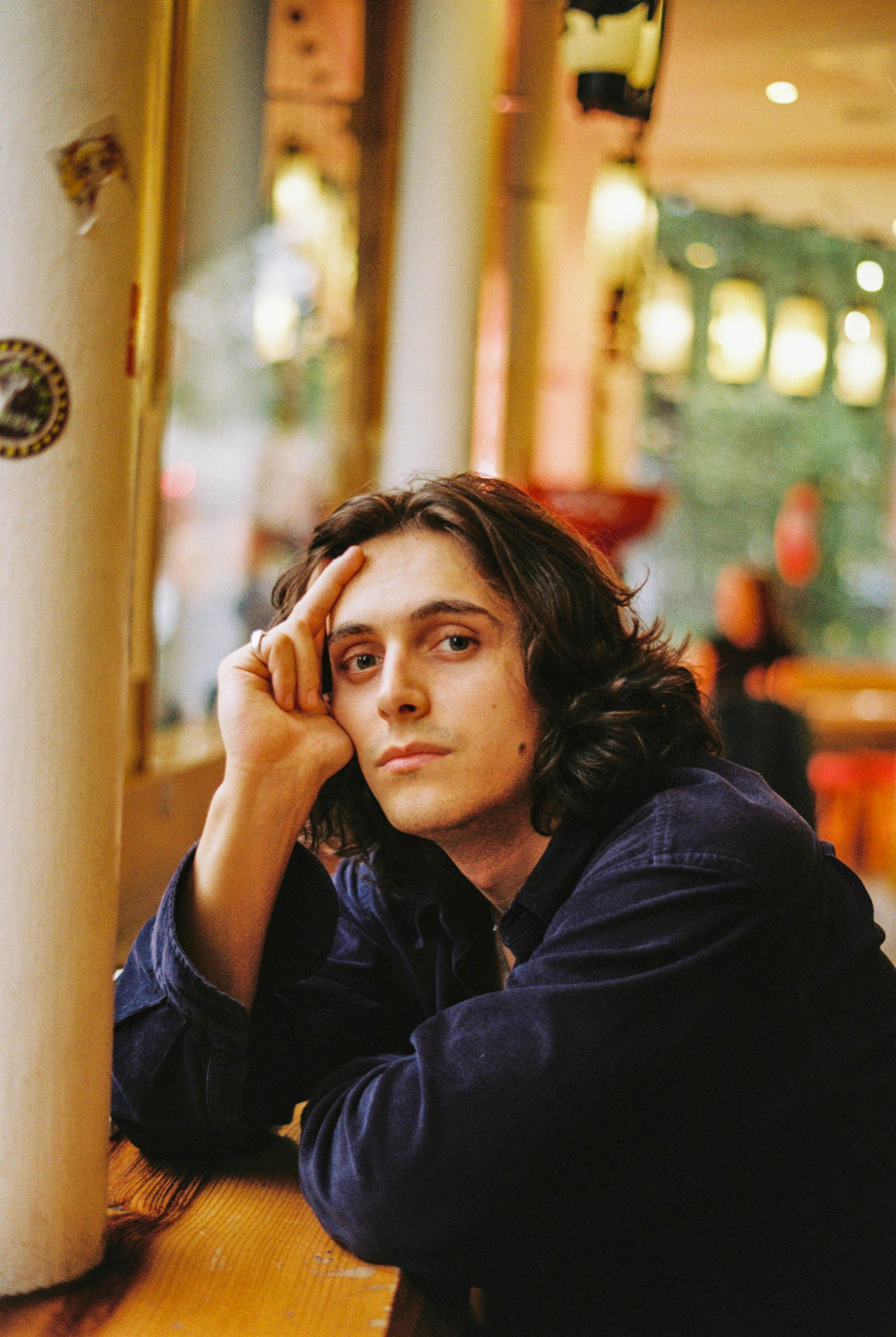

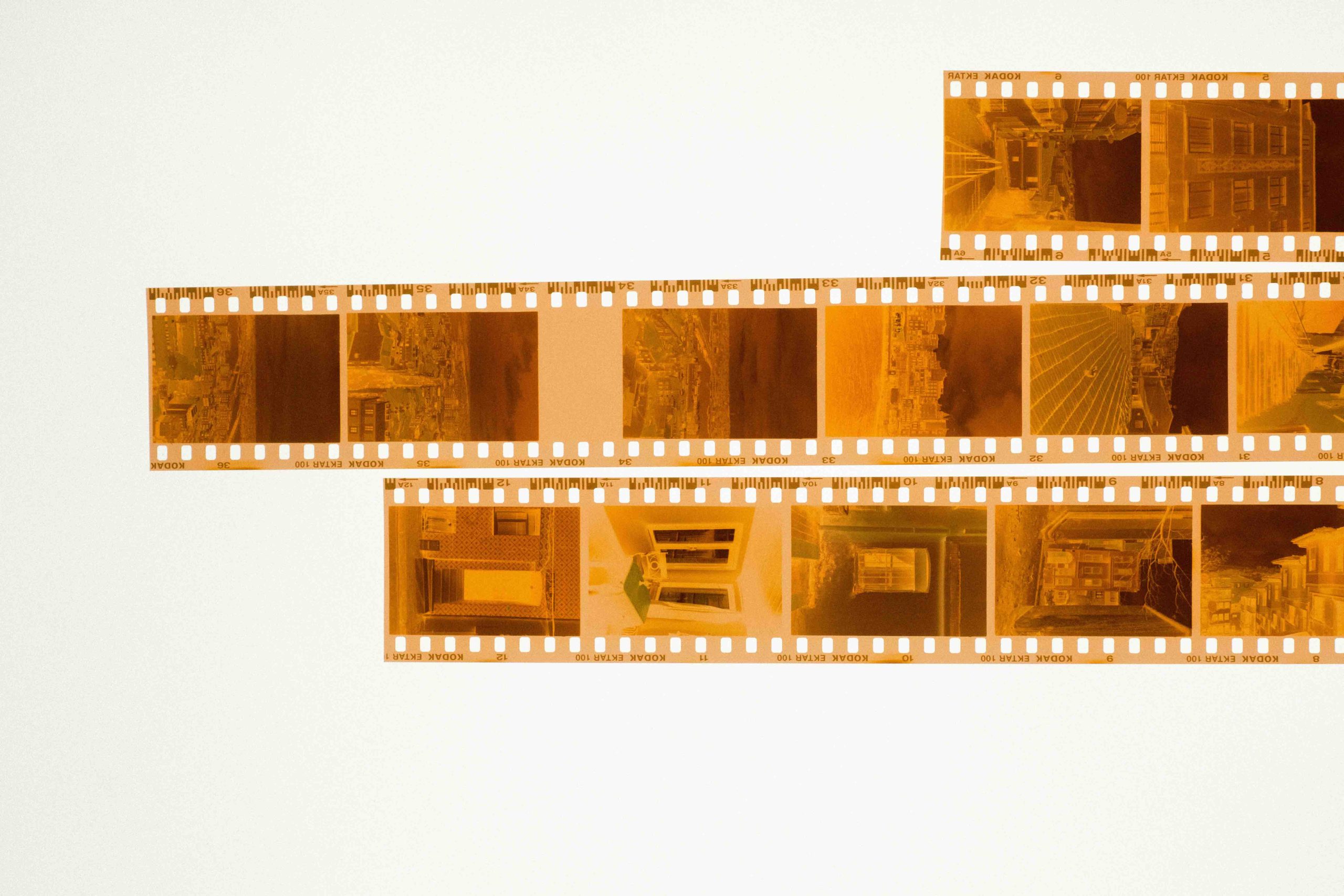

Take a look at the gallery below – these are all taken on colour negative 35mm film…

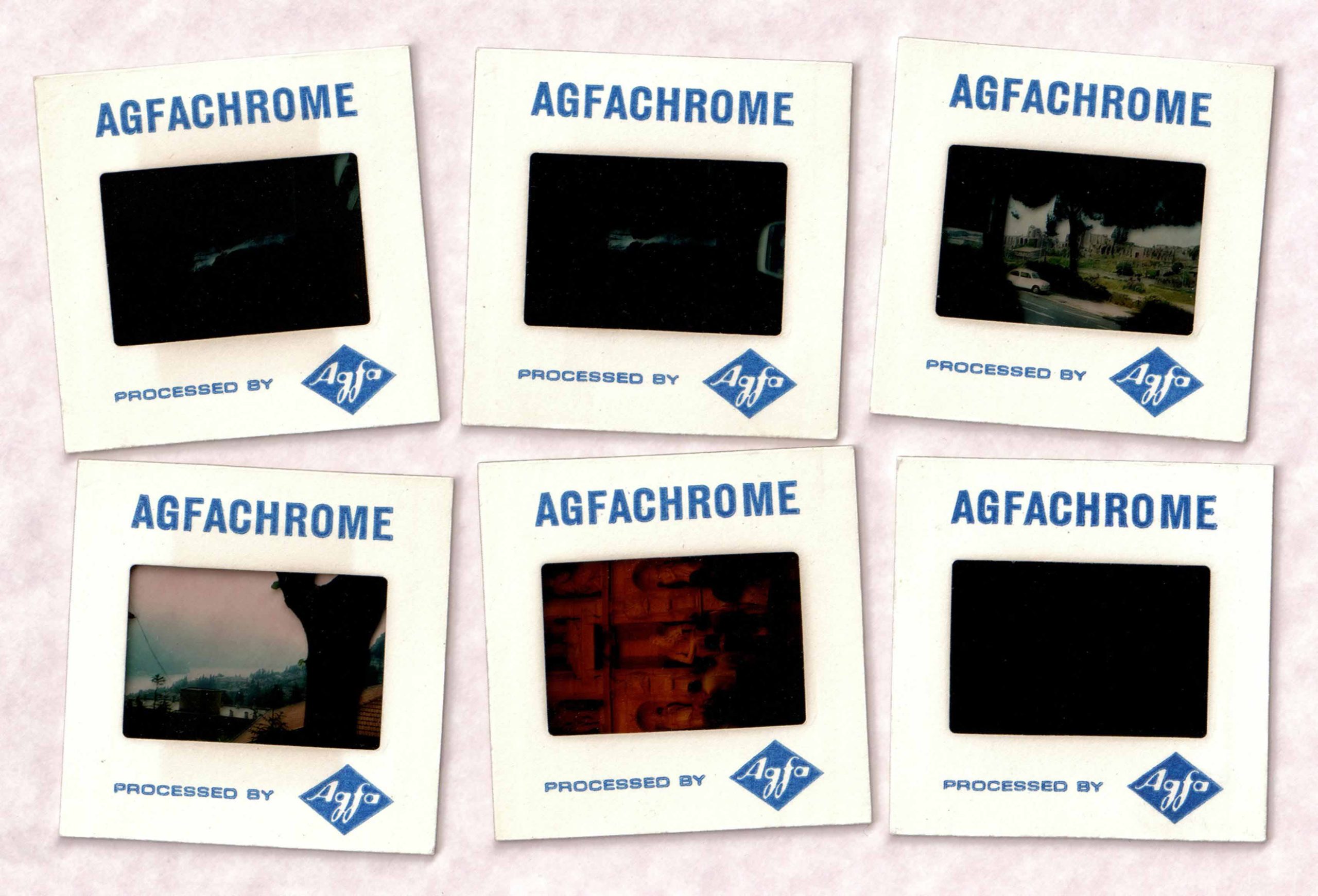

2. Slide Film (E6)

Slide film, also known as transparency or reversal film, creates a positive image directly on the film, meaning what you see is what you get. This film type is prized for its vibrant colours and sharpness but is more difficult to work with due to its limited exposure latitude.

Characteristics:

- Vivid Colours: Slide film tends to have much richer colours and more contrast than colour negative film, making it great for vibrant scenes.

- Limited Exposure Latitude: With slide film, precise exposure is crucial. There’s much less room for error compared to colour negative film.

- Popular Film Stocks: Fuji Velvia, Kodak Ektachrome, and Fuji Provia.

Best For:

- Nature and landscape photography, where colour vibrancy and sharpness are key.

- Professionals and advanced photographers who want more control and precision.

3. Black and White Film

Black and white film strips away colour and produces images that can often be more timeless and emotive in their appearance. It’s also easier to develop at home, making it a great choice for hobbyists who want to explore the development process.

Characteristics:

- Contrast: Black and white film tends to emphasise contrasts and tones, leading to moody, dramatic images.

- Grain: Different black and white films offer different grain structures, from fine and smooth to coarse and prominent.

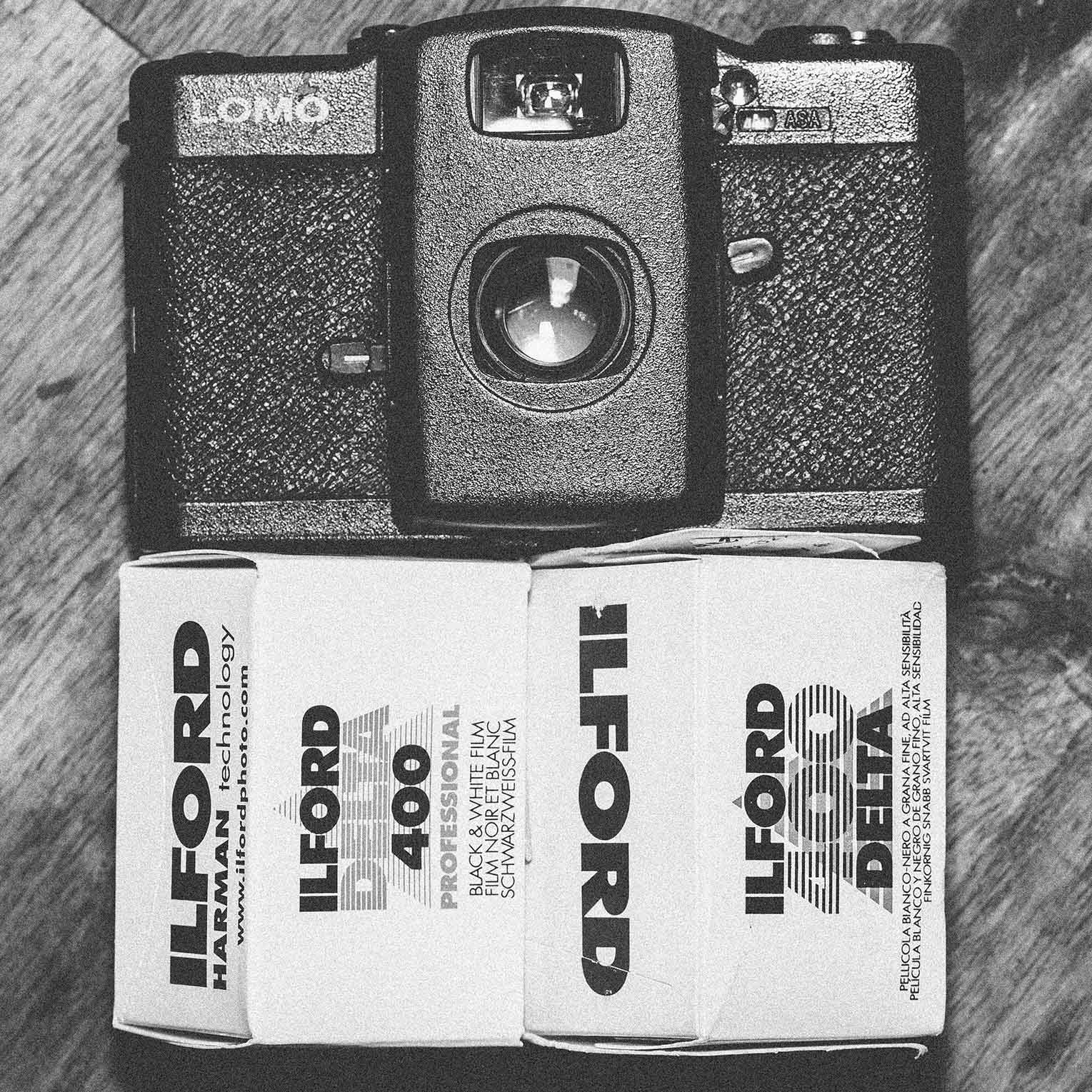

- Popular Film Stocks: Ilford HP5 Plus, Kodak Tri-X, and Ilford Delta.

Best For:

- Portraits, street photography, and artistic projects.

- Photographers looking to experiment with film development at home.

- Beginners are often recommended to start on black and white – there are pros and cons for this, but it does force you to learn contrast and composition without being able to rely on colour to “save” a bad shot!

4. Cine Film (Motion Picture Film)

Cine film is motion picture film repurposed for still photography. This type of film has a unique aesthetic, with softer colour rendering and a cinematic quality, often requiring special processing known as ECN-2.

Characteristics:

- The colour tones and contrast levels resemble those seen in films, offering a distinct and nostalgic look.

- Cine film often requires a different process (ECN-2), though many labs now offer simplified processing options (especially if you live in major cities like London…)

- Popular Film Stocks/Brands: Kodak Vision3 series (such as Vision3 500T), which is one of the most popular cine films; CineStill (CineStill works with Eastman Kodak to produce modified versions of Kodak’s motion picture cinema emulsions).

Best For:

- Photographers seeking a distinctive, film-like aesthetic with a soft, cinematic palette.

- Street photography, creative portraiture, and experimental projects.

5. Instant Film

Instant film gives you a tangible photo almost immediately after taking the shot. The magic of watching your image develop in front of your eyes has captivated photographers for decades, with brands like Polaroid and Fujifilm Instax being the most well-known examples.

Characteristics:

- Unique Look: Instant film often has a slightly washed-out, dreamy quality with soft colours and distinctive textures.

- Immediate Results: Instant film is perfect for sharing moments and creating physical memories instantly – I tend to use this most for family events and parties!

- Popular Film Stocks: Polaroid Originals (for classic Polaroid cameras) and Fujifilm Instax (for Instax Mini, Wide, and Square cameras) – note that older Polaroids, such as my Spectra AF, won’t have film directly available and you may have to rely on third party film.

Best For:

- Casual photography, parties, and events where you want to instantly share the results.

- Creative projects that play with the nostalgic, tactile nature of instant film.

6. Infrared Film

Infrared film is a more experimental type of film that captures light in the infrared spectrum, which is invisible to the naked eye. This produces surreal, dreamlike images with glowing whites and dark skies.

Characteristics:

- Otherworldly Aesthetic: Vegetation often appears white or light pink, while skies can become dramatically dark, creating an almost ethereal effect.

- Experimental Process: Infrared film requires specific filters and handling, making it best suited for photographers who enjoy experimental photography.

- Popular Film Stocks: Rollei Superman 200, Ilford SFX 200.

Best For:

- Fine art photography, landscapes, and experimental photographers.

- Projects where you want to create something surreal and unconventional.

Recommended Film Stock for Beginners

If you’re new to film photography, there are definitely some recommendations I have for a starting point…

- Kodak Gold 200: This is a classic colour negative film that’s affordable, forgiving with exposure, and offers warm, pleasing colours. It’s great for sunny outdoor shots and delivers high-quality results with minimal effort – pretty much every shot in my gallery in colour is on Kodak Gold 200.

- Ilford HP5 Plus 400: If you’re interested in black and white photography, Ilford HP5 Plus is a fantastic option. Its high ISO of 400 makes it ideal for low light or overcast conditions, and it has a classic, gritty look that adds mood to your photos. It is my favourite B/W film stock – here are shots taken on Ilford HP5 Plus.

- Kodak Portra 400: A slightly more expensive option, but Kodak Portra 400 is worth it for its exceptional dynamic range and ability to handle a wide range of lighting conditions. It’s known for producing beautiful skin tones, making it perfect for portraits.

Considerations When Choosing Film

- Film Speed (ISO): When selecting film, pay attention to the film speed, which determines how sensitive the film is to light. Lower ISO films (e.g. ISO 100) are great for bright outdoor conditions, while higher ISO films (e.g. ISO 800 or 1600) are better for low light or indoor photography. If you’d like to know more about this, see my blog on the exposure triangle.

- Grain: Grain size varies by film type and speed. Higher ISO films tend to have more pronounced grain, which can add texture and mood to your photos.

- Developing Requirements: Some films, like slide film or cine film, require specific processes, while others can be processed in the more widely available C-41 chemicals.

- Cost: This one is pretty self explanatory – #staybrokeshootfilm is a movement for a reason, but if you take a look you’ll see why I mainly stick to Ilford HP5 and Kodak Gold for day-to-day 35mm shooting!

In Conclusion...

Each type of film offers something unique, allowing you to experiment with different looks and styles, but there are definitely more suited for beginners than others.

Whatever you end up shooting, make sure you log what film and what settings you use so you can see what works and learn from your successes, and failures, with every exposure!

Let me know your favourite film in the comments below and I’ll try and shoot a roll if I haven’t already!

Fred Ostrovskis-Wilkes

I am a photographer, writer and design agency founder based in Sheffield, UK.

5 Essential Things Every Film Photographer Needs To Know

5 Essentials Every Film Photography Beginner Should Know

Quick Summary

If you’re new to the world of film, it’s easy to feel lost in a sea of information. I distinctly remember feeling incredibly overwhelmed when I got my first analogue camera and started to try and figure out what I needed to know to get out there and shooting some film.

This is my attempt to make that easy for you – In this guide, I am going to break down five essential things every film photography beginner should know.

Whether you’re picking up your first camera or simply curious about the medium, these tips will give you a solid foundation to help you create beautiful, analog images..

Key Takeaways:

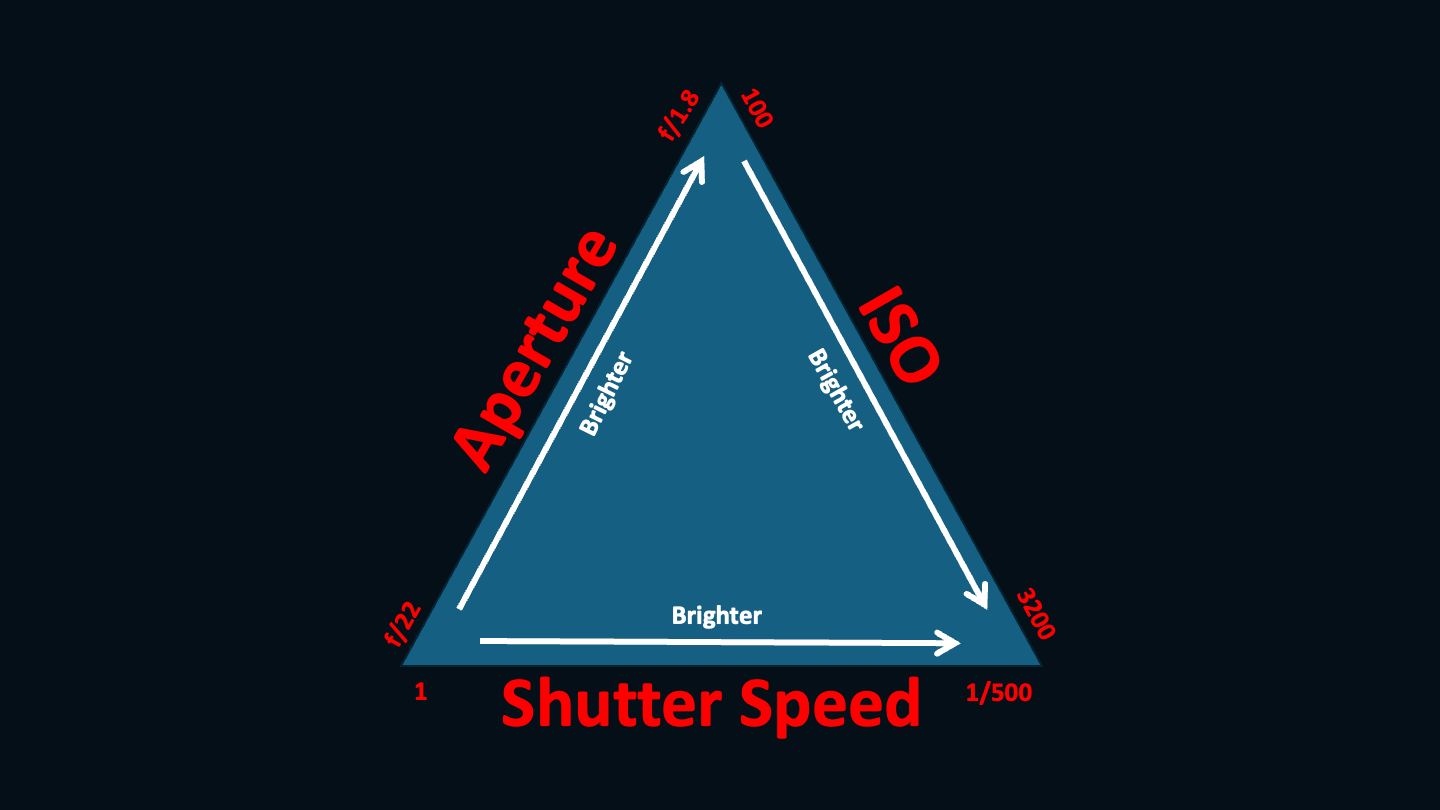

- Life gets easier once you understand the basics of the exposure triangle.

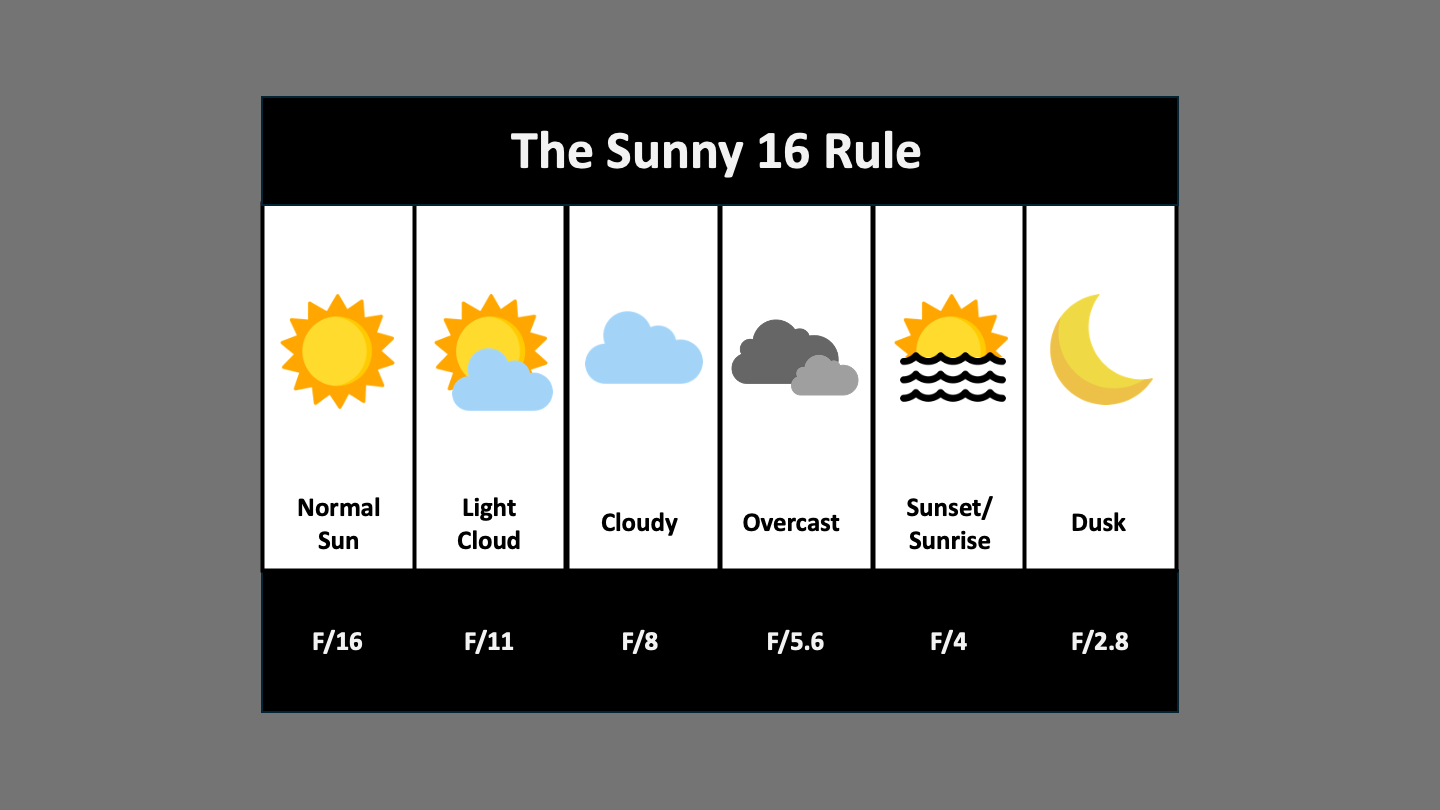

- The Sunny 16 rule will help you get shooting without metering for light.

- Metering for light will help you expose for high contrast and unstable conditions.

- Logging your shots will help you learn.

- Embrace mistakes – they’re how you can learn in the first place!

1 – Learn the Exposure Triangle

Film photography is a mad alchemy of chemicals and light – within this process, you have 3 main variables that underpin every photo you take: aperture, ISO and shutter speed. Together, these form the exposure triangle, a fundamental concept in both film and digital photography.

Understanding these three variables is essential for any aspiring photographer. By mastering the exposure triangle, you’ll not only feel more confident in your shooting but also gain the ability to make creative and informed decisions.

Put simply: aperture controls the depth of field, ISO affects your film’s sensitivity to light, and shutter speed dictates how long your film is exposed to light. The interplay between these three factors determines the final look of your image and, once wielded with confidence, can unlock your creative potential with a camera.

Mastering the exposure triangle will help you achieve better control over your shots and understand the ‘why’ behind your choices. If you want to break away from automatic shooting modes, use a fully manual film camera, and have more creative freedom, this knowledge is key.

I’ve written a full guide to the exposure triangle which you can read here – hopefully it breaks this down into something simple and digestible!

2 – Learn the Sunny 16 Rule

Once you’ve grasped the basics of the exposure triangle, it’s time to put that knowledge into practice with the ‘Sunny 16’ rule.

This is a tried-and-true method that helps photographers estimate correct exposure without relying on a light meter. It’s particularly useful if your camera’s light meter is broken (a common issue with vintage film cameras), or if you’re shooting without access to a digital light meter or app.

The Sunny 16 rule is also invaluable for fast-paced shooting, like street photography. When you’re moving quickly and trying to capture spontaneous moments, the last thing you want to do is fiddle around with your light meter and risk missing the shot.

Here’s how the rule works: If you’re shooting in bright, sunny conditions, set your aperture to f/16 and your shutter speed to the reciprocal of your film’s ISO.

For example, if you’re shooting Kodak Gold 200 film, set your shutter speed to 1/200 or the closest equivalent your camera allows. If you can’t match the ISO exactly, err on the side of caution by choosing a slightly slower speed to avoid underexposure.

As lighting conditions change, you can adjust the aperture accordingly. For instance, if it becomes slightly cloudy, drop to f/11. In full overcast conditions, f/5.6 might be appropriate, and you could go as wide as f/4 at sunrise or sunset.

As someone who lives in the north of England, I think I get to use “sunny 16” about 6 days a year, and spend the rest of it between f/11 and f/5.6…

The Sunny 16 rule is a great way to build confidence in shooting without a light meter. Just remember that it works best in stable lighting conditions, and be mindful of shadows cast by buildings or other objects.

Also, don’t forget to log your exposure settings in your analogue book so you can reflect on what worked and what didn’t (see below!)

For a more in-depth explanation of the Sunny 16 rule, here’s my dedicated guide!

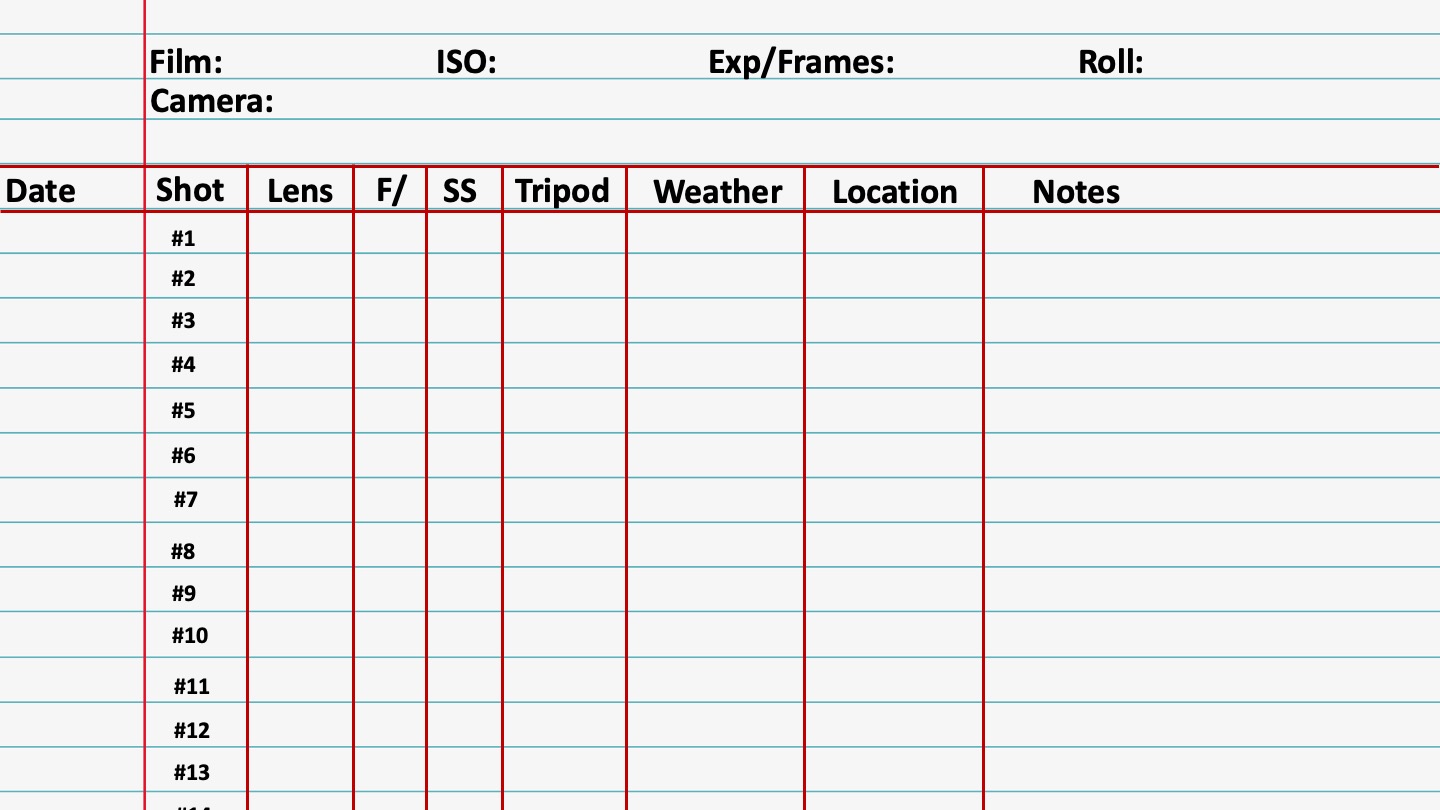

3 – Learn to Use an Analogue Book

One of the biggest differences between digital and film photography is the lack of instant feedback. With digital, every shot is accompanied by metadata: aperture, shutter speed, ISO, and more.

You can immediately review your settings and adjust or, when editing later, know what settings to use again down the line.

In film photography, however, once the shot is taken, none of that helpful metadata is saved.

This is where an analogue book (or any method of recording your shooting details) becomes invaluable. You can use anything from a dedicated app to a simple notebook to log key information such as your camera settings, shooting conditions, and personal notes.

The key is consistency. Whenever you take a shot, jot down the following: film stock, camera model, date, time, location, shot number, lighting conditions, shutter speed, aperture, and any relevant notes.

By keeping track of this information, you can compare your log to the developed film and learn from your successes or mistakes.

I know this might sound tedious, but it’s actually a lovely thing to look back on and is absolutely vital if you’re wanting to progress your understanding and ability.

Personally, I love the tactile feel of using a pocket-sized notebook to record my notes while shooting. It’s always in my camera bag, ready for quick updates.

If you’d like to know more about this, here’s a dedicated guide to film photo metadata logging.

4 – Learn How to Use a Light Metering App

Light metering apps are a lifesaver when you’re shooting with a manual film camera that lacks a built-in light meter or has a faulty one.

These apps help you calculate the correct exposure settings for any given lighting condition, giving you the ability to shoot more confidently.

There are many free and paid light metering apps available for both iOS and Android. Some popular examples include “myLightMeter” and “Light Meter – lite.”

My personal favourite is “Lghtmtr” – it’s free and ridiculously simple. Being able to tap and view/adjust the type of exposure I am after is so useful!

These apps allow you to input certain parameters, like your desired aperture or shutter speed, and will suggest the other necessary settings to achieve a proper exposure.

A key tip when using a light meter app is to decide which variable is most important for your shot. For example, if you’re taking a portrait and want a shallow depth of field, you’ll want to prioritise aperture.

Once you lock in your desired f-stop, the app will calculate the correct shutter speed and ISO to match. This is where the exposure triangle comes into play – understanding how these elements interact will make your use of the app even more effective.

5 – Accept Failure and Mistakes

Film photography is a learning process, and mistakes are inevitable. But don’t be disheartened! Every overexposed frame, every blurry shot, every roll of film that didn’t quite turn out how you imagined is an opportunity to learn and grow as a photographer.

The beauty of film photography lies not only in its results but also in the journey. Some of the most beautiful images can come from what you might initially consider a “mistake.” For instance, light leaks, unexpected grain, or even slight underexposures can add character and mood to a photo that would be impossible to replicate digitally.

The key is to embrace these moments as part of your development. Use your analogue book to document your process and analyse where things went wrong and why. Over time, this reflective practice will make you a better, more intuitive photographer. In the end, it’s all about learning from those experiences and allowing yourself the freedom to experiment.

Get out and shoot your shot!

Film photography is a rewarding but sometimes challenging journey, filled with nuances that take time to master. Please stick with it – I promise it’s worth it in the end.

Remember, each shot is a learning experience, and the beauty of film is in its unpredictability. Keep shooting, keep learning, and most importantly, have fun with your camera. Ultimately, that’s all that matters.

Fred Ostrovskis-Wilkes

I am a photographer, writer and design agency founder based in Sheffield, UK.

How to Make Your Own Film Photo Metadata Log Book

How to Use a Film Photography Log Book

Quick Summary

For many of us, the allure of film photography lies in the tactile nature of the process – the sound of the shutter, the winding of the film, and the anticipation of seeing your images once developed.

However, unlike in digital photography, metadata such as exposure settings, time, and even location is NOT recorded automatically, and once you’ve shot – it’s lost!

It’s therefore up to you to document these details. This is where the log book comes in – in this blog I break down how to easily set one up and why it’s important to do so!

Key Takeaways:

- You need to find a way that works for you, whether that’s a physical notebook or digital alternative.

- You need to track a variety of metadata such as film stock, camera, lens, conditions, aperture, shutter speed and ISO in order to learn from your shots.

- Consistency is key and will really help you progress with your understanding of how to create under different conditions.

- If you don’t know about the aperture, ISO and shutter speed, this will be harder for you. Luckily, I’ve got a dedicated guide to the exposure triangle.

Why Keeping a Film Photography Log Book is Important

Put simply, a log book helps you understand what worked and what didn’t during your shoots.

When you receive your developed photos back, being able to look at your settings and decisions for each frame can be invaluable for learning. Without this reference, you might struggle to understand why a shot was underexposed, why a specific depth of field was achieved, or why the final image didn’t match your expectations.

If, for example, you’re just tackling the Sunny 16 rule, logging your data will help you understand what works for different conditions.

By tracking each shot’s details, you’ll begin to see patterns emerge and identify what conditions or settings produce your favourite images, as well as what changes you should make next time.

This, like much of photography in general, is a process of trial, error, and reflection and is vital to you growing your skillset when wielding your film camera.

Best Methods for Logging Your Shots

When it comes to keeping a film photography log book, there’s no single way to do it. Different photographers prefer different approaches depending on their style and shooting preferences. Here are a few popular methods:

1. Traditional Notebooks

For many photographers, including myself, the simplicity of a pen and paper is hard to beat. Small, pocket-sized notebooks are a great option because they’re easy to carry around and provide plenty of room to jot down the information you need – I also like the ability of making little notes or sketches in the margins.

I typically use a small Muji notebook – they’re perfect for me!

There’s something satisfying about physically writing down the details of each shot. A small notebook fits perfectly in most camera bags, and for someone that’s trying to get away from digital when he can, it’s what I like using!

Here’s a digital mockup of how I layout my own analogue notebook…

2. Dedicated Log Books

If you prefer a more structured approach, there are pre-printed film photography log books available. These come with columns or spaces for all the relevant data, meaning you don’t have to think about what to record — just fill in the blanks. Some even include additional sections for notes on lighting, composition, or shooting conditions, which can help provide a comprehensive overview of your photography session.

I tend to avoid these as they can be very expensive for what they are and you’re forced into using someone else’s system, which might not fit your own.

3. Digital Note-Taking Apps

If you’re more of a digital native, apps like Notion, Evernote, or even a simple spreadsheet can be perfect for logging your shots.

These methods allow you to add more detail, upload reference images, and even sync your notes across devices, so you’ll always have access to your log – I can definitely see the appeal here.

If I’m honest, the humble iPhone Notes app has been a great backup when I’ve left my notebook at home, so I’d recommend that for ultimate simplicty.

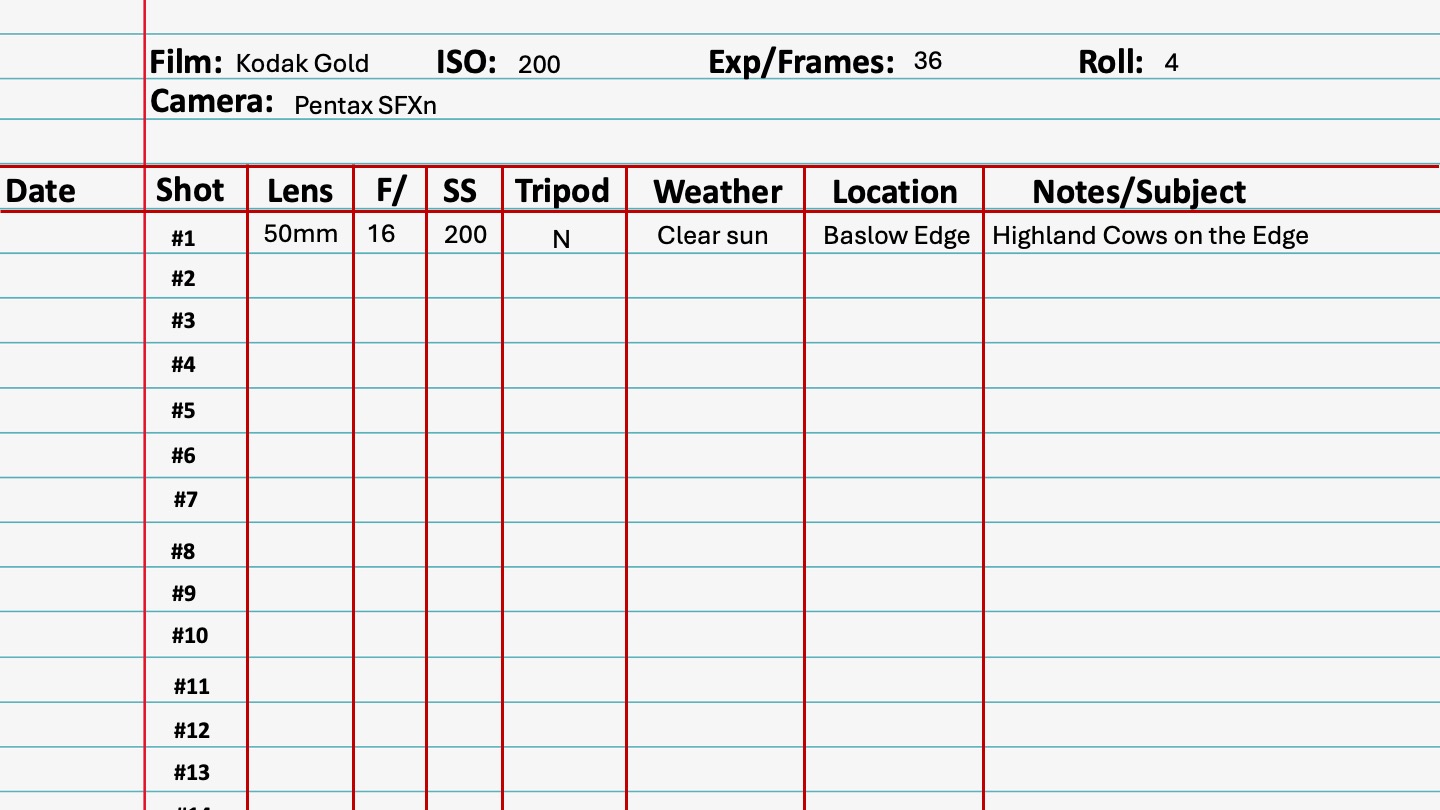

What Data Should You Log?

Whether you’re using a notebook, app, or dedicated log book, the most important part is consistency. To make the most out of this practice, be diligent in recording the following information:

1. Film Stock

This is the foundation for understanding the results of your images. Recording what film stock you used helps you determine how different brands and ISO speeds perform under various conditions.

2. Camera, Lens and Tripod

The camera and lens choice also plays a key role in the look of your image. Different lenses affect depth of field and sharpness, so it’s important to log exactly which gear you’re using if you’re flitting between glass.

I tend to use the same lens for a full roll of film, so I occasionally leave this off if I know it won’t be necessary.

It’s also important to note if you use a tripod, however if this isn’t something you do regularly, you could remove this column!

3. Date, Time, and Location

Knowing when and where you took the shot can be crucial in understanding lighting conditions. The time of day impacts natural light, and the location could include environmental factors that affect your final image.

For example, if I am out in the Peak District in the open under bright sunny conditions, then head into a shaded woodland area, it would dramatically impact my exposure.

4. Shutter Speed, Aperture, and ISO

These three settings make up the exposure triangle, and logging them is essential to evaluating your exposure decisions. Over time, you’ll begin to see how different combinations of shutter speed, aperture, and ISO create varying effects in your images.

5. Shot Number

It’s a good idea to record the number of each shot as you go along. This allows you to easily cross-reference your log book with your developed images once you receive them from the lab (and remember how many shots you have left!)

6. Lighting Conditions

You don’t always have control over the lighting, but it’s important to note whether conditions were sunny, overcast, or artificial. This helps you later understand how the lighting impacted your shot and can assist in planning for future shoots.

If you’d like to know how you can shoot in different conditions without metering for light, check out my blog on the Sunny 16 Rule.

7. Additional Notes

If there were specific challenges, like tricky shadows, unexpected movement, or if you were experimenting with a new technique, make a note of it. These personal reflections will help you learn and grow from each shoot.

I also add, for example, a column for “Distance” if I am shooting with a camera like my Rollei 35 which has zone based focusing (meaning you set the distance from 3ft to infinity in various increments).

Take a look at the below example for a log book entry for a roll of Kodak Gold 200 shot on a Pentax SFXn on a sunny day…

Why Consistency Matters

The key to successfully using a film photography log book is consistency. If you forget to jot down details here and there, it can make it much harder to learn from your mistakes or recreate the conditions of your best shots.

Try to make logging your shots a habit after each frame or at least at the end of each roll.

Using a film photography log book is one of the simplest and most effective ways to improve your skills. By understanding exactly what went into each shot, you’ll develop a deeper appreciation for the craft and grow more confident in your decision-making. Over time, your log book will become a valuable reference point, helping you unlock your full creative potential and continually improve your film photography.

Happy shooting!

Fred Ostrovskis-Wilkes

I am a photographer, writer and design agency founder based in Sheffield, UK.

The Sunny 16 Rule Explained for Film Photography

The Sunny 16 Rule Explained for Film Photography

Quick Summary

The Sunny 16 Rule is one of the most well-known methods for estimating exposure without needing a light meter. It’s a simple, tried-and-true technique that can help you get properly exposed shots in bright daylight.

In this guide, I break down exactly what the Sunny 16 Rule is, how to apply it, and the considerations you need to keep in mind.

When you’re starting out with film photography, especially if you’re working with older cameras that may not have reliable light meters, understanding the basics of exposure is crucial.

If you haven’t already, check out my guide to the exposure triangle first – this breaks down each element of exposure and will help you get to grips with necessary terminology.

Key Takeaways:

- The Sunny 16 Rule dictates that you set your aperture to f/16 on a clear sunny day and set your shutter speed to the reciprocal of your ISO

- This is great for shooting without a light meter or app or when shooting in stable conditions

- You can adjust your aperture to reflect changes to conditions and continue to use the rule (such as f/8 for cloudy conditions)

- There are considerations you need to be aware of such as being aware of shadow and contrast, and it is always good to track your metadata so you can learn from what does and doesn’t work.

- Learning the elements of the exposure triangle will help you greatly in understanding Sunny 16.

What Is the Sunny 16 Rule?

The Sunny 16 Rule is a simple exposure rule of thumb that works best under bright, sunny conditions. It allows you to correctly expose your shots by adjusting your settings without needing to rely on a light meter.

The rule is based on the idea that, in direct sunlight, you can set your aperture to f/16 and your shutter speed as the reciprocal of your film’s ISO.

For example, if you’re shooting with ISO 200 film like Kodak Gold 200, your shutter speed would be 1/200 (or as close to that as your camera allows).

Likewise, if you’re using ISO 400 film, your shutter speed would be 1/400. With these settings, you should get a properly exposed image in clear, sunny conditions.

It’s a fantastic fallback technique that all film photographers should know, especially for situations where your camera’s light meter may not be working, or you simply want a quick, reliable way to set your exposure.

I tend to use this most when shooting street photography on a fully manual camera. This is because I want to be able to shoot spontaneous subjects and events as they unfold before me, and simply wouldn’t have time to meter for these and still get chance to take the shot.

The Sunny 16 Rule in Practice

To break it down:

- Aperture: Set your aperture to f/16 when in clear sunny conditions or the corresponding value to the conditions you are in.

- Shutter Speed: Set your shutter speed to the reciprocal of your ISO, or closest your camera settings allow. For example:

ISO 100 → Shutter speed: 1/100 (or nearest depending on your camera)

ISO 200 → Shutter speed: 1/200 (or nearest depending on your camera)

ISO 400 → Shutter speed: 1/400 (or nearest depending on your camera)

Adjusting for Other Conditions

The Sunny 16 Rule can be modified for different lighting conditions by adjusting the aperture.

Here are some common adjustments:

- f/16: Direct sunlight

- f/11: Slightly cloudy but still bright

- f/8: Overcast

- f/5.6: Heavy cloud cover or open shade

- f/4: Sunrise or sunset

Remember that changing your aperture will also change your depth of field. A smaller aperture (e.g., f/16) gives you a deeper depth of field, where more of the scene will be in focus, while a larger aperture (e.g., f/4) creates a shallower depth of field, which is great for isolating your subject.

This is covered in more detailed in my guide to the exposure triangle.

How to Change Your Settings on a Film Camera

When applying the Sunny 16 Rule, you’ll be adjusting two key settings: aperture and shutter speed. The process may vary slightly depending on your camera, but here’s the general workflow:

- Aperture: On most cameras, you can adjust your aperture via a ring on the lens itself. Turn the ring to the correct f-stop (e.g., f/16 for bright sunlight, f/8 for overcast).

- Shutter Speed: This is typically adjusted via a dial on the top or side of your camera. Set it to the reciprocal of your ISO (e.g., ISO 100 = 1/100 shutter speed).

- ISO: The ISO is dictated by the film you’re using. It’s important to remember that film ISO is fixed, unlike digital cameras, so once you’ve chosen your roll of film, you’ll be working with that ISO for the entire roll. Be mindful of this when planning your shoot and choosing your film stock.

In practice, if you’re shooting on a sunny day with ISO 100 film, you would set your aperture to f/16 and adjust the shutter speed to 1/100. If it becomes a bit cloudy, you would drop the aperture to f/11 or even f/8 and adjust accordingly.

Considerations and Nuances of the Sunny 16 Rule

While the Sunny 16 Rule is a great quick reference, it’s not without its limitations. Here are some important considerations to keep in mind when using the rule:

1. Stable Conditions Required

The rule assumes consistent, stable lighting conditions. If you’re shooting in a setting where clouds are constantly moving, or there are harsh shadows cast by buildings, trees, or other structures, the Sunny 16 Rule may not give you accurate exposures.

In such cases, you may need to use a light meter app to ensure the correct exposure or adjust your settings on the fly to accommodate changes in lighting.

2. Watch for Shadows

If your subject is in shadow or partially shaded, the Sunny 16 Rule will not be accurate. For example, if you’re shooting a scene where your subject is standing under the shadow of a tree, or you’re photographing in a narrow alley where parts of the scene are shaded, you’ll need to adjust the settings to compensate for the lower light levels.

I had trouble with this in London this summer – although it was beautifully sunny, the high buildings were casting long shadows on the street and causing havoc with my exposures.

This is why it’s crucial to evaluate the scene carefully before relying solely on the Sunny 16 Rule. Shadows can trick your exposure, so be prepared to adjust as needed.

3. Depth of Field and Creative Choices

Changing the aperture doesn’t just affect exposure, but also the depth of field. A higher f-stop (like f/16) will give you a greater depth of field, meaning more of the image will be in focus from foreground to background. This is great for landscapes, but less desirable if you’re going for a portrait with a beautifully blurred background.

So, while the Sunny 16 Rule is helpful for getting your exposure right, remember that your creative choices matter too. You might prefer to open the aperture wider for artistic reasons, and when you do, make sure to adjust your shutter speed accordingly.

4. Log Your Metadata by Hand

Unlike digital photography, film doesn’t record any metadata about your settings. That’s why it’s useful to carry a small notebook or use an app to log your settings for each shot. Record details like your aperture, shutter speed, film stock, and conditions, so that when you get your film developed, you can learn from any mistakes or successes.

This process helps you refine your technique over time, and it’s especially helpful when you’re relying on the Sunny 16 Rule and need to fine-tune based on your results.

Here is my dedicated guide to creating a film photography log book!

When the Sunny 16 Rule Isn’t Ideal

While the Sunny 16 Rule is a fantastic tool for sunny, predictable conditions, there are many situations where it may fall short:

- Low-light or indoor shooting: When you’re shooting in low light, the Sunny 16 Rule isn’t going to work well. You’ll need a light meter to help you get the correct exposure, as manual adjustments based on visual estimation won’t be accurate enough.

- Highly variable lighting conditions: If you’re shooting a scene with quickly changing light, such as during golden hour or when clouds are rapidly moving, the Sunny 16 Rule can be too rigid. In these cases, a light meter can save you from constant adjustment.

- High-contrast scenes: Scenes with a lot of contrast (like shooting into the sun or scenes with both bright highlights and deep shadows) will also require a more careful approach than the Sunny 16 Rule offers. Here, spot metering or more advanced light metering techniques are necessary.

For those situations, I highly recommend using a dedicated light meter or a reliable light metering app.

It’s going to take some time to get used to it…

The Sunny 16 Rule is a simple and effective way to estimate exposure without relying on a light meter, especially in bright, sunny conditions. It’s a great rule to have in your back pocket as a film photographer, particularly if you enjoy shooting with vintage cameras or in situations where you may not have access to modern metering technology.

That said, it’s important to recognise its limitations and be prepared to adapt when necessary. By understanding the nuances and practising with different settings, you’ll be able to shoot confidently and make the most of this classic exposure rule.

Fred Ostrovskis-Wilkes

I am a photographer, writer and design agency founder based in Sheffield, UK.

Understanding the Exposure Triangle – A guide for Beginner Film Photographers

Exposure Triangle Explained: A Complete Guide for Film Photography

Quick Summary

If you’re new to the world of film photography, one of the most fundamental concepts you need to grasp is that of the exposure triangle. This blog post breaks down each element (ISO, Shutter Speed and Aperture) and how these work together to create a well exposed shot.

Key Takeaways:

- The exposure triangle consists of three critical elements that work together to control how much light reaches the film: aperture, shutter speed, and ISO (sometimes called ASA).

- Balancing these three aspects is the key to achieving well-exposed images and avoiding your shot coming out too bright (overexposed) or too dark (underexposed).

- Understanding each element will also empower you to make decisions to achieve certain creative effects in your work.

- This blog breaks down each part of the exposure triangle and how they interact with one another to shape your final image.

- Once you understand these, you should familiarise yourself with the Sunny 16 Rule – here’s a dedicated blog just for that!

Mastering Aperture: Controlling Light and Focus

Aperture refers to the opening in your lens that allows light to pass through and reach the film. This is measured in f-stops, such as f/1.8, f/4, or f/11, which are the numbers you’ll likely see on your lens or when reading descriptions of lenses.

Somewhat confusingly, the smaller the f-stop number, the larger the opening (aperture) and therefore more light is let in. Conversely, a higher f-stop number means a small aperture and less light entering the lens.

I find that aperture is often the thing that people struggle to understand, so I’ll share with you the analogy that helped me grasp it better…

Think of aperture like the pupil of your eye. When you’re in a dark room, your pupil expands to let in more light so you can see better. This is similar to a large aperture (low f-stop), which lets in more light to expose your film in low-light conditions.

On the other hand, when you step outside into bright sunlight, your pupil constricts (gets smaller) to reduce the amount of light entering your eye.

This is like using a small aperture (high f-stop), which limits the light entering your lens to prevent overexposure in bright conditions.

Just like your eye adjusts its pupil size to control how much light you see, your camera’s aperture adjusts to control how much light reaches the film, affecting the overall exposure and focus of your image.

Like all elements of the exposure triangle, it’s important to log what aperture you use so you can learn from your own shots – find out how to make an analogue photography log book here.

The Impact Aperture has on Exposure:

- A larger aperture (e.g. f/1.8) allows more light in and is much better for dealing with low-light conditions. However, this also reduces your depth of field. This means only a small portion of your image will be in focus, making larger apertures perfect for portraiture or any shot where you’d like your subject sharp against a blurred background.

- A smaller aperture (e.g. f/11 or f/16) allows less light in, and is more suited for brighter daylight conditions. This increases your depth of field, so much more of your image will be in focus and therefore typically makes the most sense for landscape or architectural photography.

It is worth reiterating that beyond just controlling light, aperture is an immensely powerful creative tool in photography and dictates how much of your shot is in focus.

Once understood and wielded correctly, this can really help you match your final exposure to the creative vision you have for the shot at hand.

Look at the below photographs.

The portrait image was taken with a larger aperture to give a blurred background effect, whilst the woodland shot was taken with a smaller aperture to ensure the scene was in focus.

Shutter Speed: Freezing Motion or Embracing Blur

Shutter speed is relatively self explanatory and refers to how long your camera’s shutter stays open when you press the shutter release button to take a shot. This dictates how much light is able to hit the film.

Shutter speed is measured in fractions of a second – if you pick up your camera and look you’ll see numbers like 1/250 or 1/30, and sometimes shutter speed is displayed without the ‘1/’ – so 1/250 just becomes 250.

A faster shutter speed (e.g. 1/1000s) means that the shutter opens and closes quickly, allowing less light in that a shutter speed of, say, 1/30, which would keep the shutter open longer and therefore let more light in.

The Impact Shutter Speed has on Exposure:

- A faster shutter speed will let in less light, but it will also “freeze” motion. This means it’s super useful for action shots or capturing any fast-moving subjects (such as sports, wildlife, automotive, etc). It is also particularly useful when you’re shooting handheld and want to avoid blur from camera shake. A faster shutter speed would also be typically used in bright sunlight to avoid overexposing your image.

- A slower shutter speed allows more light in but may result in motion blur. This can be used intentionally to capture movement, such as with flowing waterfalls or light trails, or any time you want to convey motion in your image. I would definitely recommend, if this appeals to you, to use a tripod and either your camera’s self timer function or a shutter release cable to avoid camera shake!

Using a slower shutter speed when shooting indoors, at night, or anywhere with low light conditions will allow enough light in to properly expose your film – just beware of introducing unwanted blur from camera shake.

I used a fast shutter speed in the shot below to capture the wave before it crashed!

ISO Sensitivity: Finding the Right Light for Your Film

ISO and ASA are the same thing are refers to your film’s sensitivity to light.

ISO stands for International Organisation for Standardisation, which is the body that standardised the sensitivity ratings for film and digital sensors.

ASA stands for American Standards Association, which was the earlier system used to measure the sensitivity of photographic film before ISO became the standard. The numbers between ASA and ISO were the same, but ISO replaced ASA to create a globally unified system for measuring sensitivity.

In essence, both terms refer to the same concept—light sensitivity—but ISO is the modern term, while ASA is the older one.

When you’re using a digital camera, ISO is a setting you can change shot to shot, but with film photography the ISO is dictated by type of film you’re using. There are circumstances where you may choose to alter this by tricking your camera into thinking it’s shooting with a different ISO, such as when shooting expired film, but we don’t need to cover that here.

Lower ISO values, such as ISO 100 or 200, mean the film is less sensitive to light and therefore would be more suited to daylight or brighter conditions. A very famous and common example would be Kodak Gold 200 film stock.

Higher ISO values, such as ISO 800 or 1600, mean that the film is more sensitive to light and therefore would be more suited to low light conditions and night photography. You may see that a lot of low light film photography online uses film stock like Cinestill 800T.

The Impact ISO has on Exposure:

- Low ISO Film (e.g. Kodak Gold 200) is ideal for bright, well-lit conditions. It produces finer grain (or less “noise”) and creates sharp, clean images. Whilst certainly possible to use in low light, low ISO film will struggle to capture enough light without the help of slower shutter speeds or a wider aperture.

- High ISO Film (e.g. Cinestill 800T ) is more sensitive to light and works better in darker conditions. However, the trade-off is that higher ISO film introduces more grain, which can give your images a distinct, gritty look. Some photographers love this aesthetic, but it’s something to be aware of when choosing your film.

Just to elaborate slightly on grain, as I’m aware I’ve just thrown that in without much explanation… The grainier look of high-ISO film can be used creatively, especially in low-light situations or when you’re looking for a certain mood in your photos.

It’s great for documentary or street photography when the extra grain adds to the atmosphere. On the other hand, low-ISO film gives you crisp, clear images, perfect for bright, daylight scenes like landscapes or portraits in good light.

Since you can’t change the ISO once you’ve loaded your film, choose your film carefully based on your shooting environment. If you’re going to be shooting mostly outdoors during the day, stick with lower ISO film. But if you’re shooting indoors or in low light, go for a higher ISO film, or plan to use a tripod and wider aperture.

How the Exposure Triangle Works Together

Now, if if I’ve done my job correctly, you should have a good understanding of each element. It’s important to see how they work together as a system and how changing one element affects the others.

For example…

- If you open your aperture (lower f-stop), you’re letting in more light. To maintain the same exposure, you might need to use a faster shutter speed to let in less light or lower your ISO to make the film less sensitive.

- If you slow your shutter speed, allowing more light in, you might need to close your aperture (higher f-stop) or use a lower ISO film to avoid overexposure.

- If you’re using high ISO film (e.g., ISO 800), you’re increasing the film’s sensitivity to light. To prevent overexposure, you might need a faster shutter speed or a smaller aperture.

The key is balance. If you change one part of the triangle, you need to compensate with another to achieve a proper exposure. This balance is where the artistry of photography comes in – I always recommend that you start with what is creatively the most important element and then go from there.

Say, for example, that it’s important for your shot that you have a shallow depth of field to capture a portrait, or that you want to capture motion blur to show headlights in the rain – you know you would need to adjust the rest of the elements to compensate for this creative choice.

You should learn to log your shooting settings so that you can learn from your successes and mistakes – find out how I log my film photography metadata here.

Stick With It – It’s Worth The Struggle!

Understanding and mastering the exposure triangle is one of the most important steps toward becoming a skilled film photographer. It’s learned best through trial and error – but stick with it, it will help you execute any creative vision for a shot.

If you have access to a digital camera, I would definitely recommend shooting on manual mode and experimenting with different variables so you get used to how these interact with one another without having to wait for film to be processed or incurring the cost of film itself!

Photography is both a science and an art, and knowing how to control light through the exposure triangle is the foundation that will help you take your craft to the next level.

Now that you know about aperture, ISO and shutter speed, you should check out the Sunny 16 Rule!

I hope this helps get you out there shooting!

Fred Ostrovskis-Wilkes

I am a photographer, writer and design agency founder based in Sheffield, UK.

5 Things to Consider Before Buying Your First Film Camera.

5 Things to Consider Before Buying Your First Film Camera.

Quick Summary

This blog contains all the things I wish someone had said to me when I was buying my first film camera.

To be clear, this is NOT a list of recommended cameras, there are already plenty of these kicking around Reddit, YouTube and forums.

This is a place for me to share some key considerations and thoughts before you pull the trigger and spend your money…

Key Takeaways:

- You can often get your hands on a film camera for a lot less than you think

- You don’t need to spend hundreds to get something worth shooting on

- More gear does not make you a better photographer

- Keep things simple for yourself and consider a prime lens

1 - Do You Actually Need to Buy a Film Camera?

Despite many of us growing up firmly in the digital age, it’s worth remembering that many people you know likely pre-date this technologically saturated world.

In my experience, folks tend to have relics of their analogue past tucked away at the back of drawers or boxed up in dusty attics.

To us, these objects are valuable, interesting and intriguing, but you’d be surprised at how many film cameras, lenses and accessories are just kicking around, unused and taking up space at the annoyance of their current owners.

So, before you open your wallet and start buying up gear, it’s worth asking around – reach out to parents, grandparents, friends, or anyone else who might have old film cameras and lenses.

It’s very likely that someone, somewhere, has something you can get your hands on to start shooting with.

Whether it’s given to you, lent, or even sold to you cheaply, if you can pick one up this way, I’d thoroughly recommend it.

Not only is it just nice to have a personal connection to your camera, it doesn’t really matter, at this stage in your journey, if you have the “best” camera or lens in your possession.

What matters is that you have something you can shoot with.

What you’re really after here is to be able to dip your toe into the hobby whilst limiting your financial investment until you’re sure you’d like to pursue this further.

So, if you can put a few rolls of film through one of these and start to the learn the ropes, you’ll at least be confident enough to know that this is something you want to really get into or not.

What’s more, anything you learn using this camera will be knowledge taken forward and applied to any future analogue efforts.

Any manual camera will help you learn fundamental concepts like the exposure triangle which will be vital for you developing as a photographer!

This hobby is expensive enough already, so please don’t be picky – if someone offers you the chance to get shooting for free or very little, take them up on the offer!

It doesn’t matter if this camera doesn’t feature on “Top 10 Film Cameras for Beginners” lists…

2 - Do Your Best to Avoid the Film Camera Gear Trap

More money does not mean more quality and more gear does not mean better photos.

This is worth keeping in mind at all times.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking “if I had that particular camera or lens then I’ll be a better photographer”.

Or, upon seeing your favourite Instagram photographer using a particular model, you may catch yourself thinking “if I had that gear, I could take those shots.”

The truth is, there’s only one thing that makes you a “better” photographer, whatever that means, and that’s…taking more photos.

Practicing your craft. Engaging in your own creative process. Making mistakes.

Gear envy is hard to shake – for one, the attraction of this hobby is rarely limited to the creative output of a photograph.

It is a tactile, hands-on passion and there are so many different things to try out and experiment with – new lenses, different camera models, fully mechanical, fully automatic, SLRs, rangefinders, the list goes on and on…

But, if you’re just starting out, you really need to focus on the basics before you let your eyes wander.

For one, it’s highly unlikely that you are at a level where you can really take advantage of more complicated features that some cameras have on offer.

What’s more, investing in a new lens or camera may only provide marginal gains – whereas a more experienced photographer may be able to take full advantage of these and use them to elevate their craft, you have to be honest with yourself to see if you’re in a place where you could really extract value from the additional expense.

I would look to spend as little as possible and focus my efforts on shooting film and getting familiar with core film photography elements such as the exposure triangle and the Sunny 16 Rule.

This isn’t to say if you have money to burn that you shouldn’t kick off your analogue journey with a Leica and throw caution to the wind, but you can’t buy your way to taking “good” photos and “good” photos can be taken on just about any camera/lens, regardless of expense!

The photos below were taken on a Pentax SFXn setup you can get for around £50-70 online ($60-80)…

3 - Maximise Your Film Shooting & Processing Budget.

As mentioned before, what makes you better at taking photos is the act of taking photos. To do this on film, you need to ensure you can afford film itself!

This isn’t cheap, I’m afraid – there’s a reason that #staybrokeshootfilm is a movement, after all.

So, if you’re set on buying a camera, it’s worth accounting for buying film and getting it processed when looking at the budget you have available.

In my opinion, if this is your first foray into the world of analogue photography, it’s better to spend a little less on the camera/lens combination itself and maximise the budget you have available to shoot and develop film (within reasonable limits).

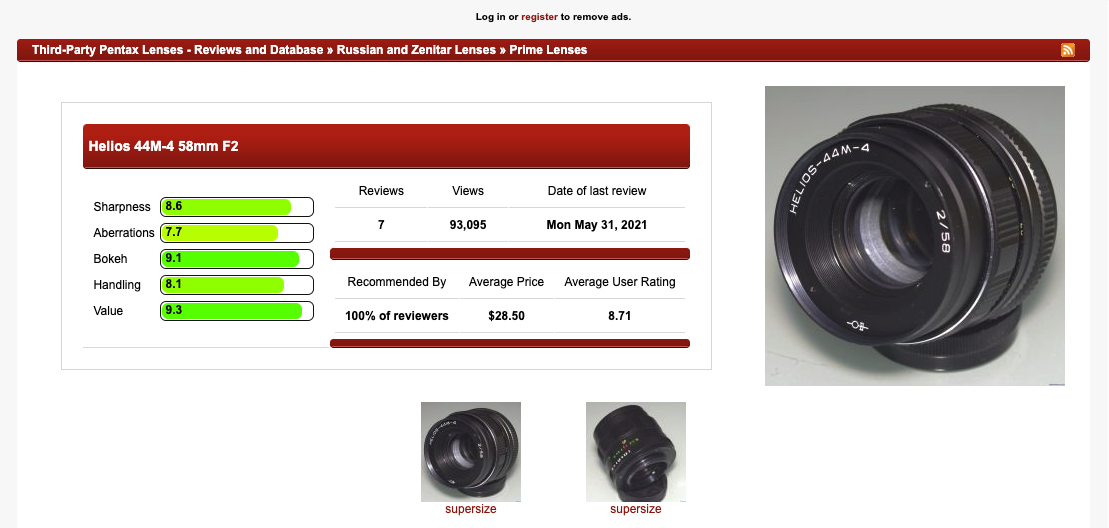

A good way to do this is to secure a camera body that is in good condition and then get the cheapest lens you can find that achieves a base level of quality.

Typically, if you just input the lens details into Google you’ll be able to see user reviews as well as shots taken with that lens – if you’re willing to dig around a bit you can get some great glass!

Here’s an example of a lens review found online – you can see it is rated for variables such as value, sharpness and handling.

Then, when you feel like you have got the hang of things a little and you know what you like to shoot, you can start to invest in lenses that suit your purpose.

If you find you love shooting street photography, you’d probably opt for a different lens than someone spending all day trying to take photographs of wild animals from a distance and vice versa.

Additionally, if you start to look outside more recognised names, you can get some absolutely great cameras and lenses for a fraction of the cost.

Ricoh, Praktica, Minolta, and a whole host of other manufacturers and brands can deliver fantastic performance and leave you spending hundreds less than more well known makes and models of similar levels.

It’s also worth noting that if you’re looking to mainly use your camera as a “snapshot” camera for documenting memories of you and your friends, you really don’t need to spend much at all.

In fact, if this is what appeals to you, you could stick to finding some cheaper point and shoot cameras or even look into half frame cameras.

Regardless, just make sure whatever you do that you’ve left enough in the bank to actually buy and process your film!

4 - Consider a Prime Lens.

The world of lenses can be incredibly confusing, especially if you’re new to photography in general and not just new to analogue.

To help remedy this confusion, and make things a little easier when making decisions on what to buy, I tend to recommend starting out with a prime lens.

A prime lens has a fixed focal length, meaning they don’t zoom. Common examples are 50mm, 35mm and 25mm lenses.

Whilst this might sound like a negative rather than a positive, let me explain…

For one, prime lenses do not have to cope with a wide range of focal lengths in the way that zoom lenses do – this means they tend to be sharper and produce “crispier” images than their zoom counterparts.

They also typically have larger apertures. This refers to numbers like “f/1.2” or “f/2.8” that you might see – confusingly, the smaller the number, the larger the aperture…

Having a larger aperture means better performance in low-light condition and also a shallower depth of field, making them perfect for things like portrait photography or when you’d like your subject to “stand out” from the background.

Additionally, prime lenses are often much smaller, more compact, and lighter, which means they’re easier to carry, use, and wield on a day-to-day basis. Due to their fewer mechanical parts, they’re also incredibly fast to focus.

All of this taken into consideration, prime lens offer powerful and versatile shooting capabilities perfectly suited to architectural, portrait, landscape, street and travel photography and, importantly, offer great value too.

Luckily, that’s about everything I shoot, hence why I use a prime lens every time I step out of the door with my camera.

However, there is one other reason why I recommend prime lenses to film photography beginners, and photography beginners in general…

They provide one less variable!

Using a fixed focus lens forces you to learn to operate creatively within the limitations of the lens. This means you’re really considering your composition and approach with each shot and, as every shot is using the same focal length, you start to “train” yourself to think in that way!

To showcase their versatility, here are 4 shots taken with the same 50mm lens…

5 - Don’t Forget About Your Local Camera Shop!

It’s easy to overlook your local camera shop in lieu of using eBay or larger retailers, but in my experience these places can be great for finding second-hand film cameras.

Shopping local can give you the opportunity to chat to knowledgeable staff who can guide you through their gear, help with repairs, and may even offer warranties on used equipment.

Typically, purchasing from an actual store is more expensive, but it does give you peace of mind that your camera actually works as well as the option of actually holding the camera in your hands and inspecting it before buying, ensuring it feels right for you.

My local camera shop is Harrison’s in Sheffield – their advice and guidance when I was starting out was incredibly valuable to me.

However, this isn’t to say you shouldn’t use eBay or similar sites.

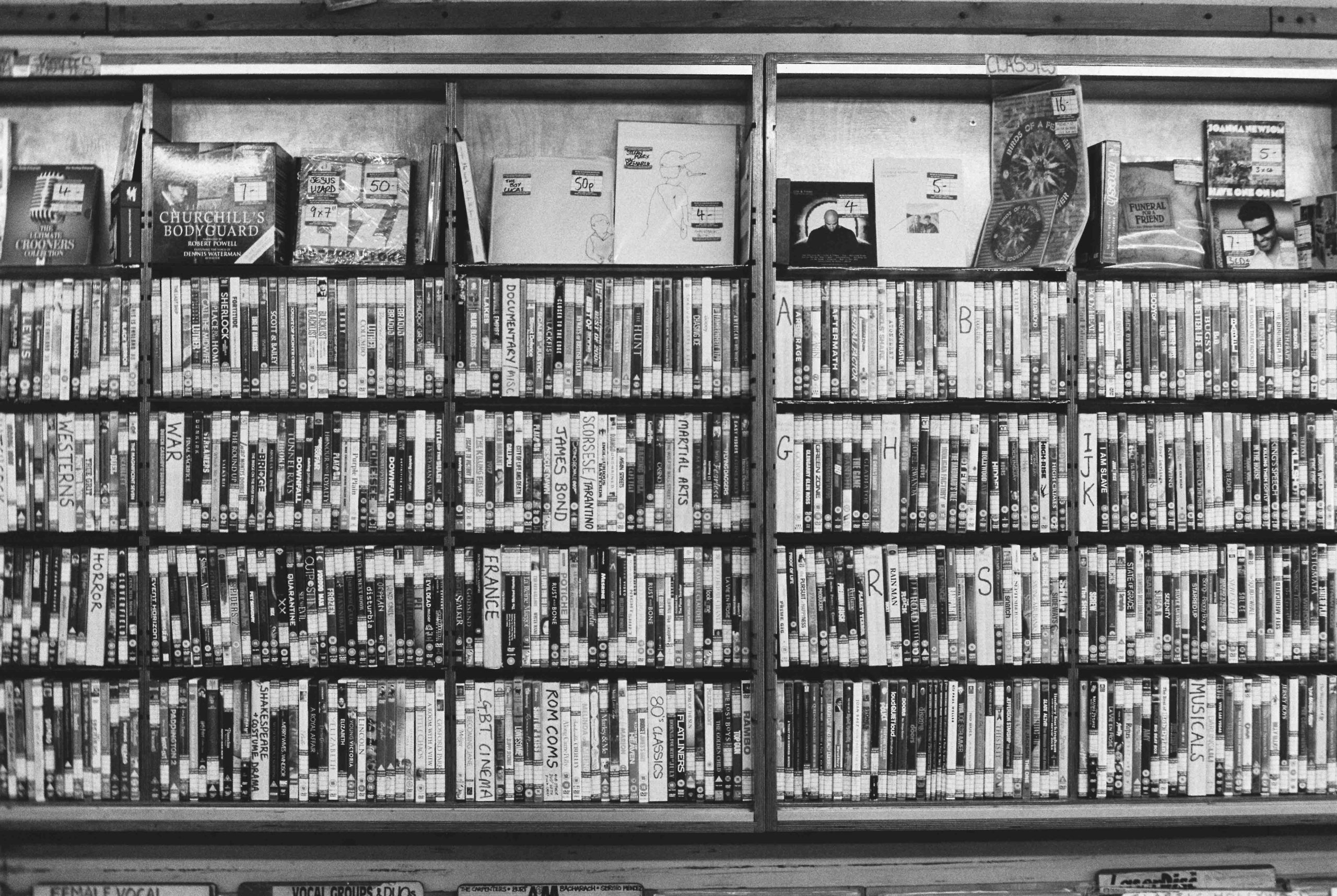

I know good friends of mine who exclusively use these to great effect, and if you’re hunting for real bargains they’re definitely where you should be looking alongside places like car boot sales and markets.

But if you’d like a bit more reassurance or guidance, pop into your local camera shop for a chat.

Online forums and marketplaces also offer more direct interactions with film enthusiasts. Often, sellers in these spaces are hobbyists themselves, eager to give detailed descriptions and fair prices to those starting out.

Plus, the conversations happening in these communities can offer valuable insights into what to look for, helping you avoid common pitfalls or spending too much just for a brand name or hype.

So, it’s worth shopping around a bit and assessing your options!

Final Thoughts...

Buying your first film camera can feel overwhelming, but it’s important to remember that photography is ultimately about the images you create, not the gear you use.

So, with this in mind, start your journey on the right foot by avoiding the hype and getting going without breaking the bank.

Take your time, explore your options, ask questions to the community, and most importantly, enjoy the process of discovering the world of film photography.

Learn fundamental concepts like the exposure triangle and ensure you’re logging your metadata when you shoot so you can become a better photographer with each and every roll.

The right camera is the one that gets you shooting!

Fred Ostrovskis-Wilkes

I am a photographer, writer and design agency founder based in Sheffield, UK.